Looking to the year ahead, how do we see the global economic landscape, and what will this mean for our region? This question is especially on people’s minds today, given the risks of deflation in advanced economies and of sustained turbulence in emerging markets.

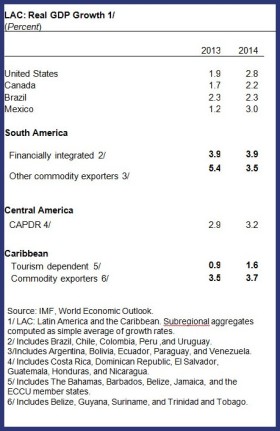

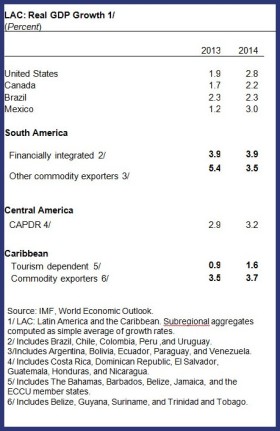

Despite these risks, we expect that the region will grow a little faster than last year—increasing from 2.6 percent in 2013 to 3 percent in 2014. Stronger global demand is one part of the story, but not the whole story; volatility is likely to be a significant feature of the landscape ahead. And regional growth rates will still be in low gear compared to historical trends, and downside risks to growth remain. So, let’s start with the global scene.

As we described in our recent

World Economic Outlook Update, we expect global economic growth to rise from 3 percent in 2013 to 3¾ percent this year, led by the advanced economies. U.S. growth would rise to 2.8 percent in 2014, as headwinds from overly tight fiscal policy and damaged household balance sheets fade, with a continued push from still-loose monetary policy and cyclical forces. Meanwhile, we see the euro area shifting from recession to recovery—following last year’s contraction, activity would expand by 1 percent. That said, the euro area recovery will be uneven, with economies under stress from high debt likely to see only a modest pickup.

We see emerging markets and developing countries as a group a bit stronger, with overall growth around 5 percent this year. China’s outlook is particularly key for Latin America’s commodity exporters. We see it growing at about the same as last year, 7.5 percent, as policies to slow credit growth and raise the cost of capital take the steam out of surging investment.

Meanwhile, commodity prices are expected to drop somewhat, especially for nonfuel items, where we see prices declining by about 6 percent over the year. Conditions in global financial markets will stay tighter than they were before the U.S. central bank’s “

taper talk” in the first half of 2013, translating into higher international borrowing costs, particularly with the recent volatility in emerging markets.

Uneven recovery

So, what does this revised forecast imply for our region? The picture varies across subregions, depending on the ways each is linked to the global economy and financial markets.

For example, thanks to the U.S. recovery, Mexico’s growth rate would rise to 3 percent in 2014. Mexico will experience both a bounce in manufacturing exports and the ongoing recovery in domestic demand, as the temporary factors that depressed demand last year continue to wane.

In Central America, stronger global demand will boost tourism and exports, and U.S. construction activity will give a lift to remittances (already growing 6.5 percent year-on-year in the third quarter of 2013). For Central America as a whole, we see growth rising from 2.9 percent to 3.2 percent this year. That said, high public debt and budget deficits are a constraint and risk to the outlook for some Central American countries.

In the Caribbean, we expect the tourism-dependent countries to recover on the back of rising U.S. activity; U.S. tourist traffic to the Caribbean was up some 7 percent year-on-year in November. That said, growth would remain low in 2014—just 1½ percent. Caribbean commodity exporters would enjoy stronger growth at 3.7 percent. But for some Caribbean countries, as in Central America, elevated public debt poses risks.

In South America, the picture is more mixed. For the large, financially-open commodity exporters (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Uruguay), average growth would remain just under 4 percent, remaining in low gear by historical standards. The uplift from global demand will be counterbalanced by weaker commodity prices and somewhat tighter financial conditions. Among these countries, domestic conditions will matter a lot for the outlook. For example, Brazil is running up against supply bottlenecks that are constraining output and pushing up inflation, so we see its growth no higher than last year, 2.3 percent.

For other commodity exporters in the region, the picture is less favorable. In Argentina and Venezuela, pressures on inflation, the balance of payments, and foreign exchange markets developed in 2013. These pressures are weighing on confidence and aggregate supply.

New (and old) risks

And for all the countries in our region, the global economy still holds risks. Very low inflation in advanced economies could cause inflation expectations to drift downward, generating rising real interest rates (with short term rates near zero) or deflation in those economies. In addition, weaker emerging markets growth could hit commodity markets. Financial stability risks include rising corporate leverage, as well as pressure on asset valuations if interest rates rise more than expected. Also, sustained turbulence in emerging markets could tighten global financial conditions further.

Indeed, and a little paradoxically, we have fairly high confidence that the outlook features a lot of uncertainty. We see several major shifts going on in the global economy, such as the growth handoff from emerging markets to advanced countries, the unwinding of stimulus in advanced countries (and the Fed’s move towards the “exit” from extraordinarily accommodative monetary policy), and the rebalancing in China. Each of these shifts could present speed-bumps that could trigger volatility. So policymakers will need frameworks that are flexible, nimble, and resilient to ride out any shocks that might emerge.

In sum, while growth is picking up, we should expect more turbulence for our region. Hence, policymakers in Latin America and the Caribbean should not rest easy just yet. Rebuilding fiscal buffers, and using monetary policy and flexible exchange rates to absorb shocks where possible, remains the order of the day. Steps to strengthen medium-term economic policy frameworks would be helpful in some countries as well. Keeping a close eye on financial systems for signs of strain will be essential too. And finally, structural reforms to education, infrastructure, labor, and product markets will need to be pursued—throughout the region, including in the United States—to move growth to a higher and more sustainable pace over time.

via:http://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2014/01/30/the-outlook-for-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-in-2014/